Segelflug-Video 2023 – With the Ventus 3 in the Alps – fantastic pictures – accentuated by music

In the Cockpit with Patrick Gabler

Segelflug-Video 2023 – With the Ventus 3 in the Alps – fantastic pictures – accentuated by music

In the Cockpit with Patrick Gabler

This time, we’re kicking things off with a hot topic: How can I recognize good weather conditions? This first part is about optimal preparation so you don’t miss out on a fantastic day. If you’re planning a cross-country gliding trip, you can of course just take off and see where the thermals take you, or search until you find the right path and then arrive roughly where you wanted to go. Our two flight reports show how both can be a great experience. Sometimes the very first flight experience can spark a passion, as was the case for a young pilot in Canada who talks about her training. Of course, skill is also required when you find yourself upside down for a moment: during aerobatics against in front of Eiger, Mönch, and Jungfrau. It’s also breathtaking in the far north, where you can enjoy unique views at extreme altitudes (and temperatures) at the Vågå Wave Camp. In terms of climate, the teams in the 20-meter two-seater class in Brandenburg had to brave the opposite, namely a heat wave – but they still had fun. Flights in L’Aquila in central Italy also offer this, where you can marvel at two seas at the same time during a flight. Perhaps on your next flying vacation? But as always: safety first. This time, we introduce you to the new Power FLARM Flex, and our “How to” section covers the basics, risks, and pilot errors when aborting takeoff. We’ll stick with takeoff, specifically the winch, and optimize it by examining the influence of rope length on release height in more detail. We also have a little bit of technology: first, we take a look at how modern wind measurement technology makes thermals visible, and then we take a look at the development of gliding instruments. So, now you can relax a little – and dream a little about the coming season and many wonderful flights. And now: click here for the current issue!

Curious about what’s inside? Here’s a preview:

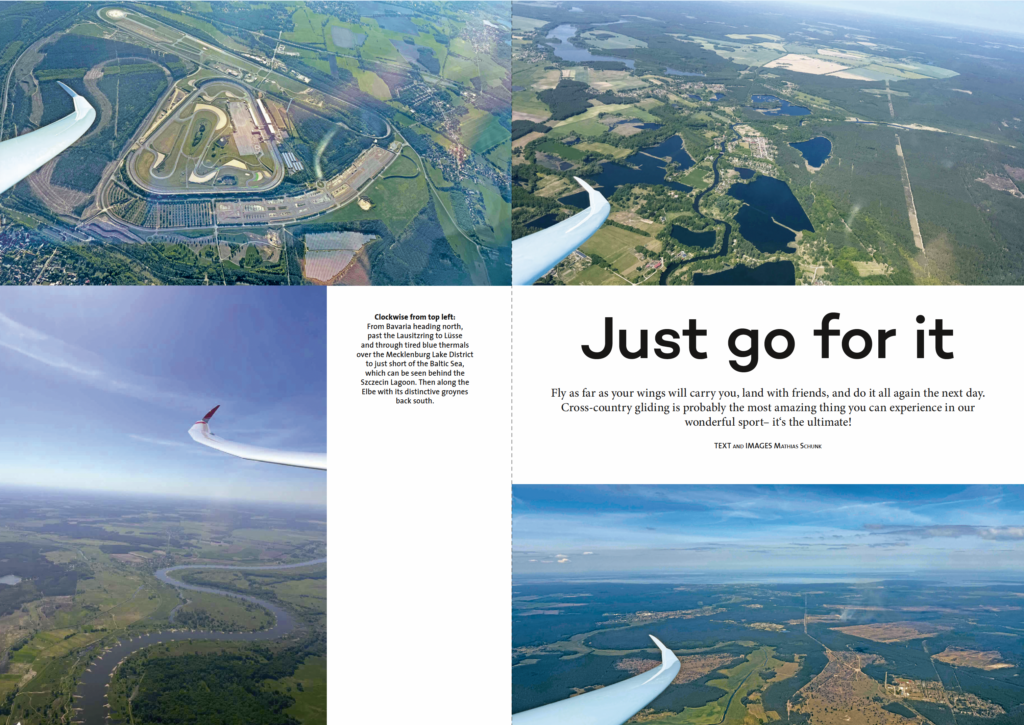

For me, 2025 will certainly go down as the year of cross-country gliding. It all started after the Bundesliga flight on May 11, when Armin Behrendt suggested that we could go cross-country gliding starting tomorrow. Up until then, I had only checked the unpromising Alpine weather for the next few days and hadn‘t looked at the lowlands, which, on closer inspection, turned out to be quite promising. So we agreed to meet tomorrow morning to set up the Arcus, in which Armin was to fly with Markus Eggl. A quick look at the weather showed the clear direction: first east past Munich and then north, destination uncertain, although the word “Lüsse” had already been mentioned in the morning. Without a motor, however, the cross-country gliding trip would have ended for me after just 12 miles at Lake Tegernsee. Okay, the Bräustüberl by the lake is always nice.

As soon as we flew towards the mountains, the comments in the various WhatsApp groups started. Tassilo Bode made the pertinent remark, “Guys, north is about 170 degrees to the left!!!!” Or, alluding to Armin‘s off-field landing during our last cross-country gliding flight near Suhl, “Petra, hook up the trailer, this is going to go wrong.”

In fact, contrary to our original plan to fly east of Salzburg, we left the mountains behind us quite quickly and soon found ourselves in rather poor flatland thermals. East of Munich, conditions slowly improved and we made rapid progress northward. We continued over the Upper Palatinate Forest towards the Ore Mountains. Unfortunately, coming from the south, we arrived a little too low over the Ore Mountains for my liking, and our differing perceptions of this became apparent once again when Armin asked whether we should fly west or east around Dresden, while I was actually just busy getting air under the wings. Later, over the Elbe, I enjoyed the view of the impressive Elbe Sandstone Mountains again from a relaxed altitude.

The clock now showed 4:45 p.m., and we still had about 125 miles to go to Lüsse. Knowing how good the area between Klix and Berlin is, this was entirely realistic.

Shortly before 6:30 p.m., we landed in Lüsse as planned and were warmly welcomed by Thomas Bonsack, who was there with his Oldenburg club for a flying camp. I would like to take this opportunity to apologize once again to FCC Berlin for my initially somewhat annoyed flight comment in WeGlide. The member, who had apologized several times for the €49 landing fee, had made a mistake, and we received an email from the board stating that the landing fee in Lüsse for cross-country gliders was €0 and that we would be refunded the excess fee.

The next day, we started planning our flight over breakfast. Since I believed that every cross-country gliding flight should include some kind of special highlight, and I had flown over the English Channel on one of my last flights, I suggested that we fly to the Baltic Sea this time. We would then fly east of Berlin to the south, towards the Giant Mountains, and then perhaps on to Prievidza. However, the tough blue thermals made the Baltic Sea plan somewhat difficult. We made slow progress over the Mecklenburg Lake District.

You can read the entire article in our current issue.

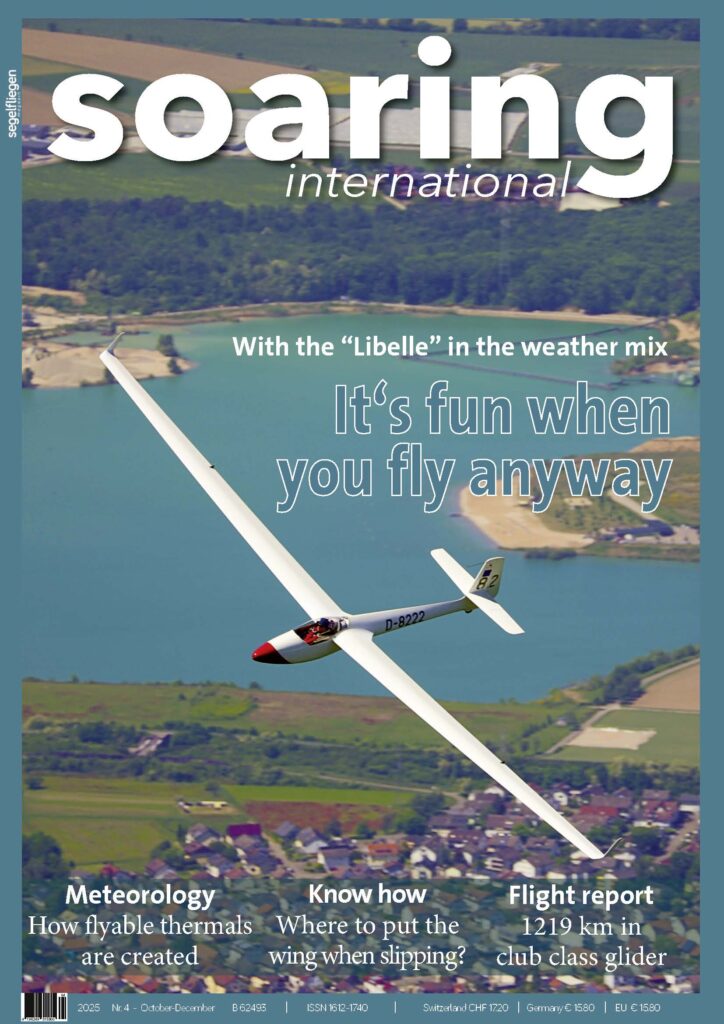

Here it is, our latest issue! Once again, we have put together a colorful selection of exciting, fascinating, and informative articles for you. These include some fantastic cross-country flights: with a Libelle in mixed weather, 1,200 kilometers with a club-class glider, a road movie with the Stemme, and a daring flight with the ASK 18. Our Sposos also report on their summer of performance flying, our meteorologist explains how workable thermals are created, you will learn where the wing should point during a slip and how wind influences an optimized winch launch. A pilot whose accident ended without serious consequences reports on how important it is to assess the terrain, especially in the mountains. Our oldie fans can look forward to the Skylark “Feldlerche”, which is becoming a star as an oldie, and those who enjoy reading about history will be taken back to the beginnings of the motor glider era and the long road to the B13e turbo-electric glider. Of course, there is also news, including the successor to Easy Memory and the IRIS All-in-one from LX Navigation. And finally, something to dream about, a visit to a gliding painter.

So, now let’s get to the current issue!

And now let’s have a look into the current issue:

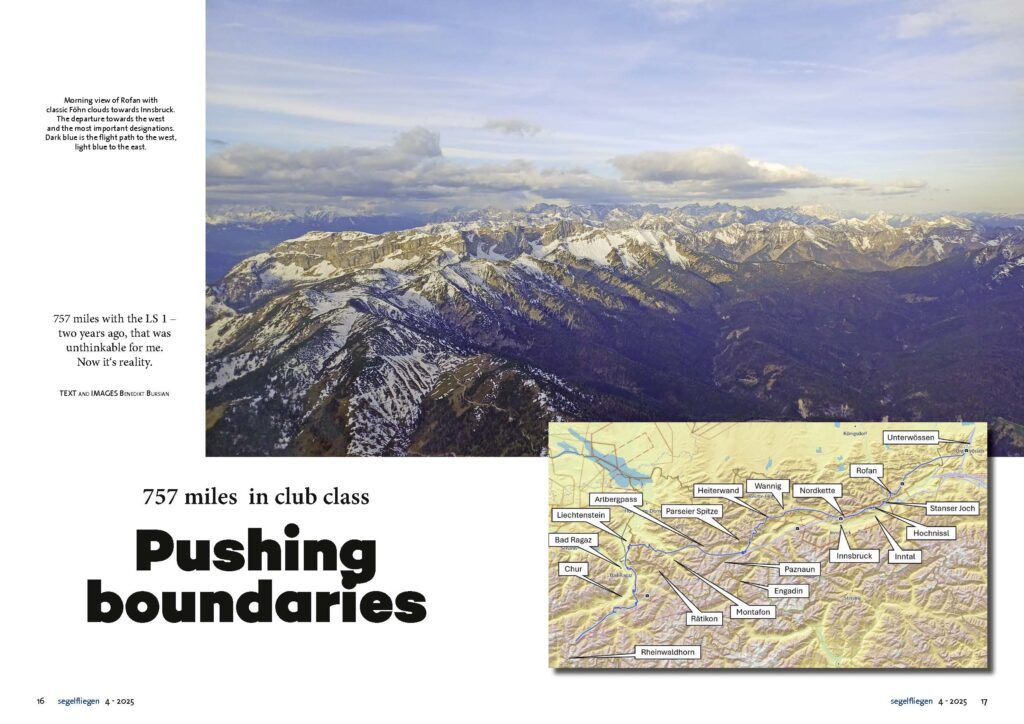

757 miles with the LS 1 – two years ago, that was unthinkable for me. Now it‘s reality. But let’s start at the beginning.

It‘s a normal day at university. I‘m sitting in the lecture hall, feeling a little bored, and scrolling through the weather maps for the coming week. My mood slowly lifts when I see that in a few days, a cold front will move southward from a low-pressure system over Great Britain, heading almost directly toward Biscay. In the Northern Alps, that means a day of foehn winds is on the way! And in April, that means the days are already significantly longer than in fall or spring, when statistically most Föhn conditions occur. I analyze further weather models and they all agree: there will be Föhn on Tuesday and Wednesday.

The next lecture starts, but I can‘t get the idea out of my head. I start planning in my mind. A day off requires some logistical planning. The first problem is finding the time, which means no exams, no mandatory internships, and no important events on that day. Luckily, Easter and the Easter semester break are just around the corner, so I‘m sure to have time. You also need an aircraft that is equipped to fly in a jet stream, i.e., with an oxygen system and transponder.

Fortunately, I have been the proud owner of an LS 1-f neo, the “8Y,” for several years now, which meets all my requirements. The only drawback is that it is a club class aircraft, built in 1974. It has no water ballast, no flaps, and the yellow zone starts at 92 kt (170 km/h), which can be a problem with wind speeds of up to 65 kt (120 km/h) and the strong turbulence that can be expected. And last but not least, you also need an airfield from which to take off. I use Unterwössen for this, from where I can be sure to be in the air by 7 a.m.

The plan

As the days pass, Wednesday emerges as the most likely best day. In the morning, the wind field should be far enough east to be reachable from Unterwössen. In the east itself, the wind will not pick up until late afternoon, but good thermals are expected to set in from 12:00 noon. Experience has shown that the combination of wind and thermals is particularly good, as the thermals adjust the air stratification so that the wind does not flow around the mountains, but over them. In addition, the wind organizes the thermal detachments on the windward slopes of the mountains, creating a race track, especially on the long southern slopes of the Kalkalpen in the east.

The plan is therefore to make the first turn as far west as possible. On the one hand, this has the advantage that the tailwind leg back towards the east becomes longer, and on the other hand, I will arrive at the slope lines just in time for the start of the thermals. The next turn should then be as far east as possible in order to re-enter the wave system of the main ridge, which will then be in the wind field, so as to be independent of the end of the thermals. My PC ultimately shows 673 miles (1,083 km) over three turning points, which should be possible!

The flight

7:04 a.m., I‘m sitting in the plane, the tow plane tightens the rope, and we‘re off! (…)

What happens next? Read the full article in the current issue.

segelfliegen magazine issue 03-2025 is here!

Once again, a wealth of interesting and informative articles await you: After a review of AERO 25, we accompany Sebastian Kawa on his adventurous journey to Pakistan, where he flew over K2. An expedition like this requires a huge amount of preparation – but even a “normal” cross-country flight in southern Germany is no walk in the park. So what goes into a 2,011 km flight? Of course, you can’t do without thermals, which is why our meteorologist explains why you can find great thermals under cumulus clouds. We’ll tell you how to find the right path when flying low over the Ardennes and why the final approach has to be spot on in the gliding paradise of Namibia. In the Pilot’s Report, we take a closer look at the Duo Discus. We continue with the SPOSOS, who report on their first three months, and young glider pilots who spent an exciting week at the Fayence gliding camp. The accident involving a young pilot in a Swift shows how important it is never to overestimate your abilities. For our vintage aircraft fans, we have been following the restoration of the LOM 57/1, and for clubs, we have a few tips on how to foster a positive club culture. To ensure that winch launches go smoothly, we explain the wing area and rope weight required for approach, while for F-towing, turning is an important maneuver. Finally, we look back to 1894, when the first two gliding clubs were founded.

Don’t want to miss out on anything? Click here to subscribe!

And you can read a little preview now:

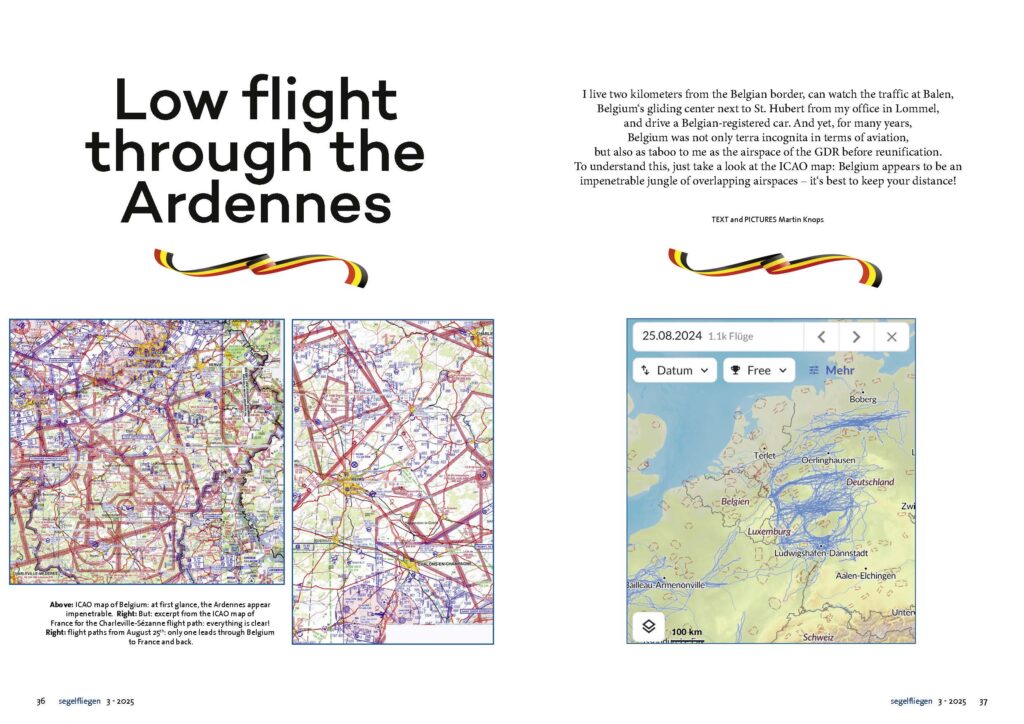

I live two kilometers from the Belgian border, can watch the traffic at Balen, Belgium‘s gliding center next to St. Hubert from my office in Lommel, and drive a Belgian-registered car. And yet, for many years, Belgium was not only terra incognita in terms of aviation, but also as taboo to me as the airspace of the GDR before reunification. To understand this, just take a look at the ICAO map: Belgium appears to be an impenetrable jungle of overlapping airspaces – it‘s best to keep your distance!

My ambition to change this was sparked by several flights by Hermann Leucker, who fearlessly entered Belgian airspace from Leverkusen, crossed the Ardennes, and returned safely! So it had to be possible somehow! I spent the next long winter evenings searching the internet for information. Here are two links that will help you quickly find your way through the jungle:

Summary: It is not recommended to fly through Belgium during the week. The airspace above 4,500’ is reserved for military use. Below 4,500’, the airspace is generally uncontrolled and therefore open to gliders, but there are a number of restricted areas whose status must be checked before flying in, for example via notam.info.

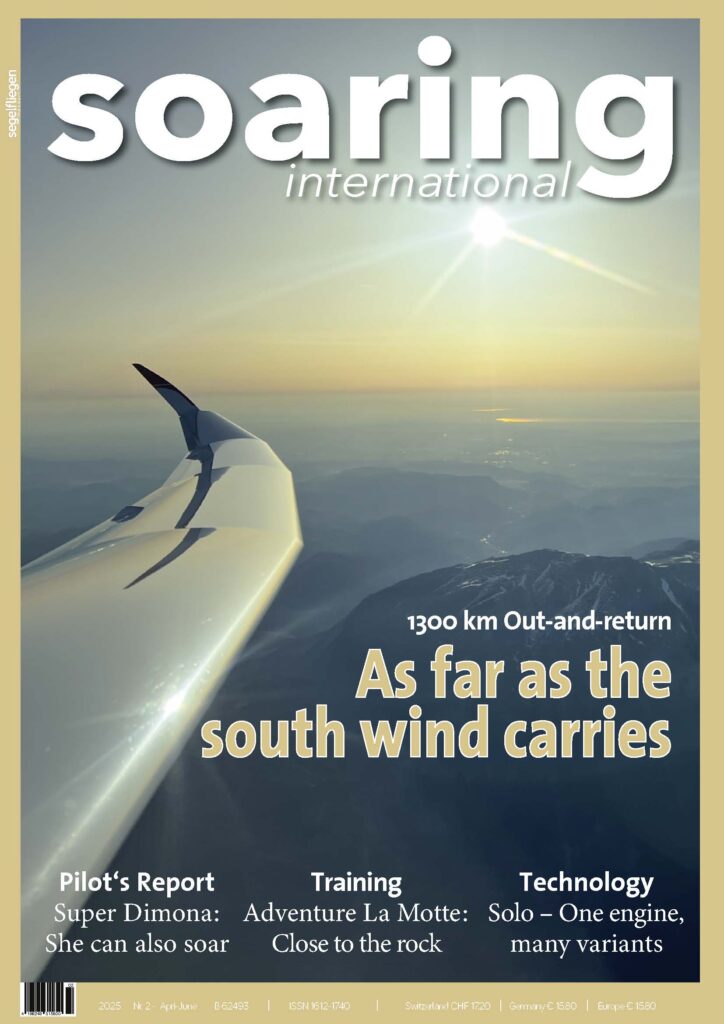

The situation is completely different at the weekend. Outside the vicinity of the few large airports (and with the exception of a few restricted areas), the entire airspace up to flight level 55 or higher (often FL75) is uncontrolled and free! All the necessary information can be found on the gliding association‘s website in a compact and easy-to-understand format. It‘s just like always: once you know how it works, it‘s really simple. And so, when the weather conditions have been right, I have flown through Belgian airspace quite often in recent years. This was also the case on August 25, 2024.

Topmeteo had been forecasting perfect weather for days. At first, I didn‘t want to believe the “hole” that was predicted for the Bergisches Land region in the morning. Why? And how can you predict something so local three days in advance? But it was true! So, I made a quick decision at the start and instead of flying east as originally planned (which worked out wonderfully a little later in the day), I flew southwest towards Belgium. This made sense anyway given the extremely low base at the start (2,000’ / 600 m MSL). Destination: Sézanne Airfield, in the middle of France, east of Paris and a good 30 miles / 50 km southwest of Reims.

Airspace in France

So I would also have to deal with French airspace. This puts many German glider pilots off in much the same way as Belgian airspace. However, on closer inspection and with a little preparation, many of these concerns disappear…..

What happens next? Read the full article in our 03-2025 issue.

Breathtaking images taken on board of Arcus Alpha Mike with Alberto Sironi and Andrea Venturini during the second day of the race. Enjoy watching!

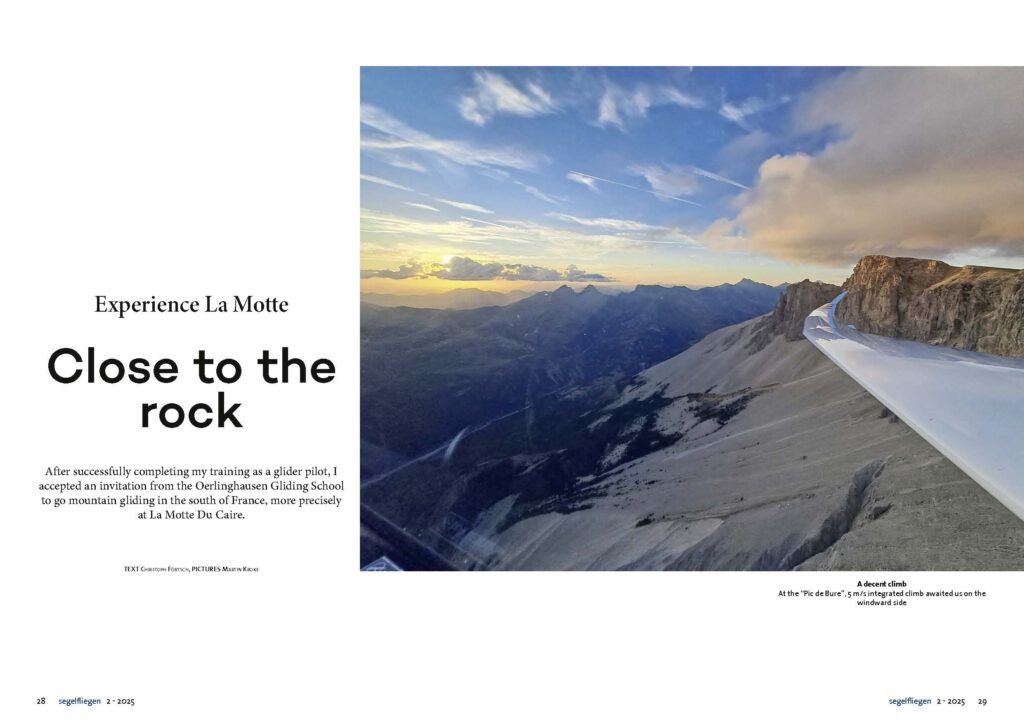

Here it is, the latest issue with lots of exciting and interesting articles! As it should be, we start with flight preparation, and there’s something completely new in terms of checklist management. We then start with a series of fascinating flights: first in a two-seater along the Alps from east to west, as far as the south wind will carry us, then we try the other side of the Wiehengebirge, Wesergebirge and Ith mountains and set off on another flight – without much hope but with a lot of courage – towards France. A bit of a mountain, you think? Ok, you can practise that with the Oerlinghausen Alpine Gliding School in La Motte; you can train everything here in a safe area with a flight instructor, from aerodromes to lee waves and cross-country flying. The SUST investigation report on the accident on the Julier Pass shows how important this is – you can learn a lot from it. The weather is of course always an issue and we take a closer look at why cloud thermals are better than blue thermals. However, success in competitions requires a lot more, as our team proved at the World Championships in Uvalde – we take a look behind the scenes. Of course, gliding is also a wonderful experience beyond competitions and track records, for example in a Super Dimona. Our author has extensively tested the touring motor glider. The technology freaks among you can look forward to the experiences of aircraft manufacturers and glider pilots with the solo engine, and to finding out about the factors that influence the optimum winch launch. Then it gets a bit spooky at night in the museum – we accompany a photo project at midnight between “Skull Splitter” and “Vampyr”… In our portrait, the blue mop of hair of Elena Fergnani, the Italian pilot with the hearty laugh, is not spooky but simply funny. Have fun reading!

Get the latest issue at the newsstand or directly from the publisher!

And here is a look at the current issue:

After successfully completing my training as a glider pilot, I accepted an invitation from the Oerlinghausen Gliding School to go mountain gliding in the south of France, more precisely at La Motte Du Caire.

As a young pilot of 25 years old and with just a little more than 100 launches, I was initially unsure whether I was mature enough for this adventure. However, my concerns were batted away by the flight instructors: “Of course, come with us! You always fly with a flight instructor anyway.”

Since signing up, my excitement and anticipation increased week by week. I tried to prepare for what awaited me in the French Alps that week with relevant literature on mountain gliding.

In mid-August, I finally set off. With a packed car, I drove about 600 miles to La Motte, stopping overnight in Weil am Rhein. I received a warm welcome at my accommodation and immediately felt very comfortable in the hotel, which was situated in an old mountain village. Only the language barrier caused me some concern. Here my choice of Latin as a second foreign language took revenge on me. But thanks to a smartphone with a translator, this was not too much of a problem.

Lots of new impressions

The first day of flying was upon us. After a good breakfast, I set off for the airfield and met the other pilots and the flight instructors for the first time. The briefing took place in front of the clubhouse, and the weather conditions and forecast for the day‘s gliding were conveyed to us without any additional images or maps. After that, we came together as a group and discussed how the four aircraft would be divided up for the day. The Oerlinghausen Flight School had brought two ASK 21s, a Duo Discus XL and an Arcus M.

After extensive instruction on the ground, the gliders were winched up at midday to reliable thermals. Flying so close to the slope is daunting, and it quickly becomes clear that you would be in over your head here alone. The local mountain “Blachère” is the first step of a staircase that carries the gliders from La Motte into the mountains. However, contrary to expectations, it is not the thermals at Blachère that carry the gliders, but a thermal lift above the airfield.

The impressions during this first flight in the mountains were overwhelming. The geography could not be more different from the area around Oerlinghausen and I didn‘t know where to look first. After almost two hours, the memory was full. The new impressions, this different way of flying – after almost two hours, I asked my flight instructor to slowly fly back towards La Motte. The detailed debriefing helped me to process everything I had experienced and whetted my appetite for the next day.

You can read the full article in our current issue. Enjoy the read!

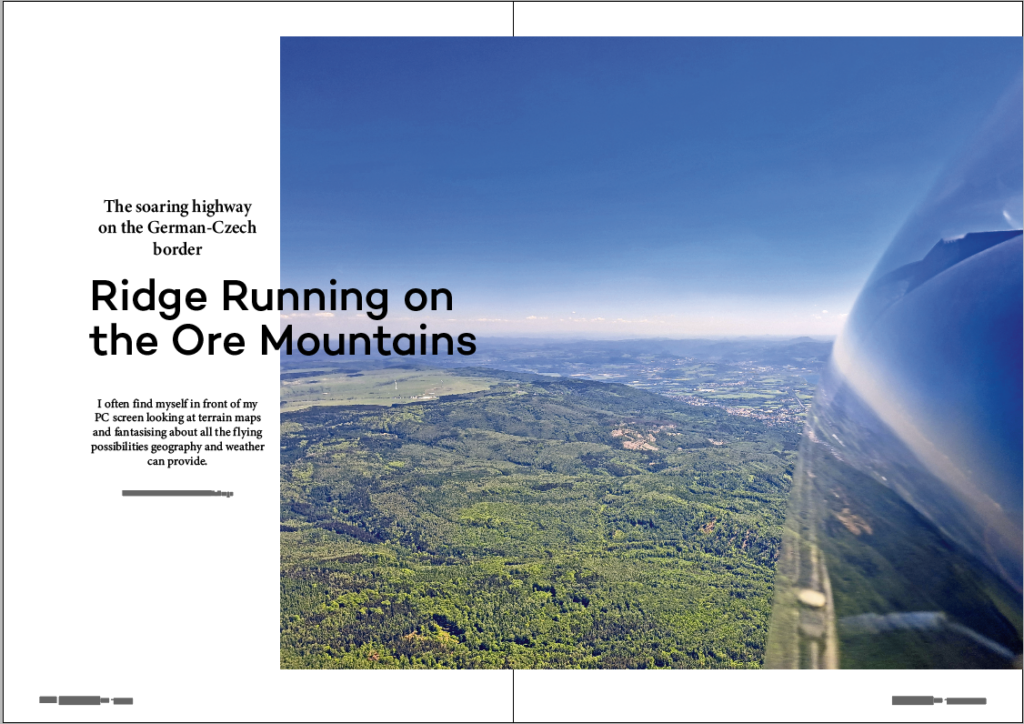

Our authors have once again been extremely busy and have put together interesting, exciting and educational reports for you. Let’s start with high-altitude flights – never fly above 3000 meters without oxygen. Find out here what you need to bear in mind. Then we head to the racetrack along the German-Czech border on the windward side of the Ore Mountains and then accompany a flight across Germany covering 1400 kilometers in two days – and all the while with clean wing edges, right? Do bug wipers really do what they promise? After this report, things are heating up as we experience the “big class” World Championships in Uvalde, Texas, first hand. On the subject of safety, we learn from a failed landing of an LS4. That soaring should be above all fun is proven by our “date” with a sensitive flying machine, the Hütter 17. For those who prefer power, we introduce the Wankel engine: how does the aircraft manufacturer, the technician and the pilot judge it? Now you feel like learning to fly a glider? At over 40 or 50? No problem, as our report shows, because there is no age limit for gliding. As always, we haven’t forgotten our specialists: which parameters influence a winch launch? The focus here is on release height and safety. Finally, we get to dream a little, first about the unique flying experience in Namibia and then about “flying in” over rugged peaks and azure lakes near Sondrio. If you’re quick, you can still secure a place for March 2025! After so much reading material, it’s time to relax: our columnist tells you something about hunter-gatherers today… And now: look forward to the new issue – and if you haven’t subscribed to the magazine: pick it up at the newsstand or order directly at the publishing house.

Take a look at the current issue:

I often find myself in front of my PC screen looking at terrain maps and fantasising about all the flying possibilities geography and weather can provide.

As gliding has been practised in Germany for so long, coming up with new possibilities is a difficult task. After a little research you will most likely find out that someone at some point has already tried what you are envisioning as a possibility.

My Motivation

My story about ridge flying on the Ore Mountains started a few years earlier in November 2019 when during the winter I was checking for opportunities to lengthen the normal gliding season through the winter. A south-easterly wind situation was potentially bringing the possibility for wave flying in the lee of the Ore Mountains and so I started preparing for this event days in advance. After contacting FC Großrückerswalde airfield I made all necessary preparations days in advance (oxygen, airspace check, study terrain, etc.).

After a few years of “hunting” for these kind of special weather situations I learnt a few lessons the hard way. It rarely happens that a forecast is consistent days in advance and usually the weather forecast changes quite a few times until the big day comes. It turned out that the weather forecast deteriorated so much that there was no wave forecast in the Ore Mountains anymore.

Well, trying is half the fun, and succeeding is the other half. By this time, I had already studied the terrain maps of the area and I started questioning whether the windward side (for south-easterly wind conditions) would not provide enough ridge lift to fly along the entire length of the Ore Mountains. A year later, at the 2020 Schwerewelle Symposium, I heard for the first time of the possibility of flying the ridge on the Ore Mountains, and suddenly, my idea comes back to mind.

The weather

So what kind of weather do we need to accomplish a ridge flight in the Ore Mountains? Let’s first have a look at the terrain maps of the region. The ridge line can already be seen standing out in the map below and it spans from south-west towards the north-east. Looking at the ridge orientation, in order to use ridge lift along the Ore Mountains, south-easterly winds are needed. A direction of 152 degrees (give or take) looks ideal and a wind speed of 20 kt should be comfortable enough to keep the glider aloft along the ridge line, even in the areas where the ridge profile is not ideal. Lower wind speeds (15 kt) should also work but I do not know how well this will work on the entire ridge (for example some areas have a less good ridge profile).

In the meantime I was not the only one thinking of flying along this ridge and in 2023 Jan Rothhardt has made a beautiful flight exploiting this weather conditions along the Ore Mountains. A look at the surface pressure charts from two days (20th of March 2023 when Jan Rothhardt flew 540 km at 116 km/h and 15th of May 2024 when Ralf Andrich flew 281 miles at 62 kt) with good conditions along the slopes reveal a low-pressure system above central Europe. The anti-clockwise circulation of the low is bringing the south-easterly winds in the area of the Ore Mountains flowing perpendicular to the ridge.

But how often do we encounter south-easterly winds during the year? A quick look on Windfinder will show us that the weather station at Tušimice/Nechranice reports no predominant south-easterly winds during any month of the year. Therefore the south-easterly winds are not a common event in the area.

The flight

Going back to springtime this year, from the 9th to the 15th of May I was on a small gliding Safari through Germany. I was already for a few days at Bayreuth airfield, and looking at the weather situation, the thermal PFD’s were decreasing day by day, and the outlook was not too optimistic. Some thermals in the weather forecasts, but nothing really great. A quick look at the wind forecasts and I am immediately struck by the strong south easterly winds reported in the area (…)

Exciting? Ok, you can read the whole article in the current issue, which you can order here.

Andrea Venturini met Riccardo Brigliadori at the airport shortly before his return to Italy and spontaneously recorded an interview with him.

Listen to it here

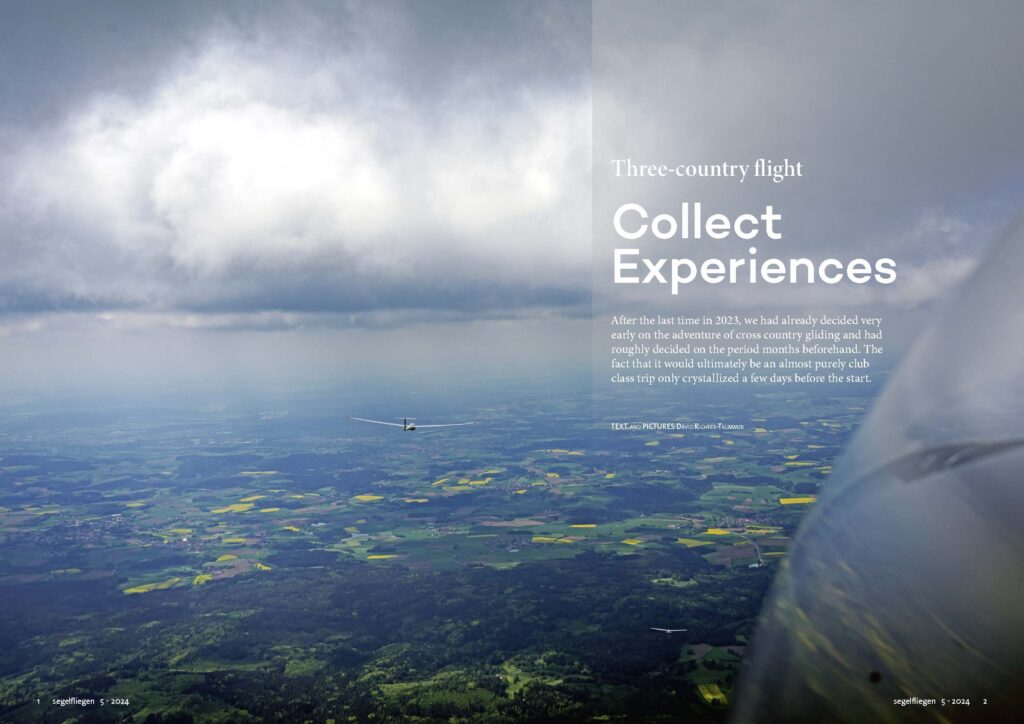

What can you look forward to in the current September/October issue? For example, there’s an exciting three-country flight without an engine, but with spectacular northern lights in the Allgäu region. Another flight takes you over the sea to a small island as a turning point – a gliding challenge that requires precise planning, but then offers unique views. There is also a unique gliding airfield in the Philippines, where an enthusiastic glider pilot has set up a flying operation under palm trees with great dedication. The two-seater Grand Prix in Aalen did not take place under palm trees, but under thick rain clouds. Our Pilot’s Report explains how you can still make it to the top of the podium. A second Pilots’ Report deals with the DG 800B, an airplane that has already had a few years under its wings but cuts a fine figure on long distances. Whether long or short distances, nothing works without thermals, and in our article we take a closer look at them: eleven points form the basis for your thermal flying tactics and an ideal centering aid can be generated from this knowledge. However, you can evaluate the thermals by combining numerous measured flight data with ground type and land use; this is particularly helpful for young pilots. If you would also like to have a special foehn behavior explained: here you go, we also have an interesting short report on this. For the technology freaks, this time we tried out how the ACD-57 instrument cluster proves itself in everyday flying and what “speed cameras” on the aircraft can do. We also cover the topic of safety: if you’re in the cockpit in hot weather, there are a few things to consider before, during and after the flight. Finally, we finish off with the B12 over Berlin and a story from the cockpit. Enjoy reading!

And now: look forward to the new issue – and if you haven’t subscribed to the magazine: pick it up at the newsstand or order directly at the publishing house.

And now a brief look at the current articles:

When I booted up the computer on Monday morning after our hiking glider flight, I realized: goal achieved – I‘ve forgotten my company password. The impressions of our experiences were still buzzing around in my head, too deep, too strong and omnipresent. Everyday life was simply too far away from me to take possession of me again. My thoughts were still on flying….

My WSF WhatsApp group for 2024 had already been recycled from the previous year and we agreed on 10 days at the beginning of May as a rough time frame in which we wanted to do something again. All interested parties had allocated time for this period – as far as could be planned – and were on standby, so to speak, waiting for my starting signal.

Why May? Well, in May the world is open to a touring glider pilot on the northern edge of the Alps. This means that the south, i.e. Slovenia to northern Italy, is usually still easy to fly as long as it is not raining, because the air mass is usually still cool and active enough to be able to leave the Alps and reach them again. In principle, the north and east are also easily accessible during this time. Above all, however, all glider pilots are scrambling to get into the air as soon as possible. Therefore, almost everywhere, if the weather permits, there is a flight operation that you can join.

When cross country flying flying without a motor, the weather forecast over several days and good geographical knowledge are very important. I then sit in front of my maps and think about what would probably be feasible. Simply turning up as an uninvited guest on foreign sites, perhaps even as a larger group, often presents the hosts with major challenges. That‘s why you can‘t count on being able to take off early, gather the group and fly off together.

The end of each flight is also always an exciting affair. Choosing a suitable location with the right infrastructure, good weather conditions and accessibility simply takes time. Due to the delay at the beginning and end as well as the necessary consideration for the group and correspondingly defensive flying to make an outlanding very unlikely, this usually leads to quite short individual distances.

But that doesn‘t matter, because here in Europe, for example, even just 400 km in one direction usually changes the landscape, culture, country and customs considerably. But what remains is the enthusiasm for gliding and for crazy activities. That‘s why as a touring glider pilot, regardless of whether the person at the destination airfield speaks French, Italian, Czech or German, you are generally welcomed with great hospitality.

But back to the start. A low pressure system over the Gulf of Genoa once again brought days of heavy rain to the central and western Alpine region. In the east, however, drier cold air continued to flow in, which led to a very distinctive weather boundary. On Thursday, 09.05.24, it should become increasingly drier and more thermally flyable from Micheldorf to the east and northeast. Although a clear northerly component in the wind was still to be expected, which should cause congestion in the Alps, I expected the alpine pumping to be absent, which should make it possible to overcome the Danube valley even with the very low base of less than 2000 m in the direction of the Waldviertel.

As is so often the case, the Czech Republic and Germany should go well anyway, only for the following Friday a more strongly braking CI screen was expected in the central and eastern Czech Republic. Friday 10.05.24 should then be very good in Germany and Saturday/Sunday enough to somehow make it home again.

Was I supposed to drive people crazy with this rather mediocre forecast? Well, it seemed possible, you only get further by doing, so ok, let‘s ask who would be there … Arcus M not available, DG 800 has just sent the defective engine to Solo … so there you go. Markus Zingerle with his 301 Libelle was very eager and accepted immediately and Till Berthold with his Ventus Cm was also there. Fits, a fine, small group with people who can fly and are independent enough to manage on their own in the event. That was exactly to my taste (…)

Exciting? Ok, you can read the whole article in the current issue, which you can order here.

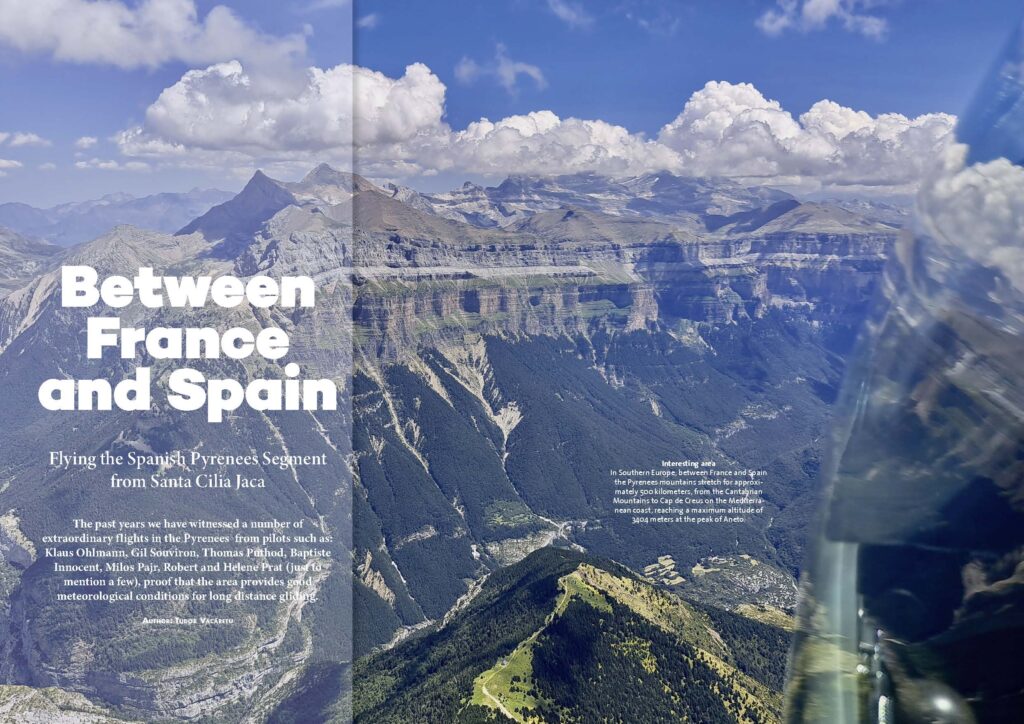

Here we are: the latest reading fun for gliding freaks: we have lots of great articles for you in the new issue! We start with a look back at Aero 2024, where gliding took part again for the first time, learn how to fly safely on a slope in our cover story and see whether thermals really always rise vertically. Our author then takes you to the Pyrenees between France and Spain, where we learn how to analyze data from glider flights and why motor glider pilots should pay particular attention to their flight preparation. Then it’s off to the south of Australia, where gliding can be experienced in seemingly endless space without many restrictions. But there are also great views very close by, namely at Lake Constance, where an airfield borders directly on a nature reserve and where “normal” flights can also be enjoyed. Is this the future of gliding? Or spectacular flights with top equipment? It’s amazing what young glider pilots have told us. And finally, a look back to 1924 to three daring men in their flying boxes.

And now: look forward to the new issue – and if you haven’t subscribed to the magazine: pick it up at the newsstand or order directly at the publishing house.

And now a brief look at the current articles:

Along the Pyrenees are a number of gliding airfields which are active through the normal gliding season. On the Southern side are the Spanish airfields of Santa Cilia Jaca and La Cerdanya. On the Northern side the following French airfields can be found: Puivert, Saint Girons, Bagnères de Luchon, Saint Gaudens, Tarbes, Oloron, and Itxassou. On the Central axis of the Pyrenees, on the Eastern side, the French airfield of La Llagonne is situated, possibly the highest European gliding airfield with an elevation of 1711 meters.

The general weather situation in the Pyrenees is of Northern circulation with most of the rain falling on the French side while the Spanish side sits in the rain-shadow staying dry and sunny. During the months of July and August thunderstorms can develop late in the afternoon or in the evening most commonly when the wind blows from the South during the hot summer days. Further there are numerous microclimates along the mountain chain and where to find the best weather can be difficult to predict.

From the point of view of the glider pilot, all forms of lift can be expected while flying here: ridge, thermals, wave and convergence. The best form of lift for long distance gliding flights in the Pyrenees is of course wave lift, encountered with Northerly and Southerly winds. However, long distance flights can be done with thermals as well in the Pyrenees, a good example here serves the flight of Gorka Elduayen www.onlinecontest.org/olc-3.0/gliding/flightinfo.html?dsId=8532752&f_map= with a performance of 823 kilometers.

The standard gliding flight route in the Pyrenees (give or take) is from Santa Cilia Jaca to La Cerdanya or the other way around, confirmed also by the WeGlide segment: Pyrenees.

Last summer I had the chance to fly from Santa Cilia Jaca and fly the entire WeGlide Pyrenees Segment in thermals. Located in the Western Pyrenees in the Aragon Valley, at an elevation of 684 meters with an asphalt runway (direction 09/27) of 850 meters Santa Cilia offers air-tow possibilities.

The basic strategy here is either to take a high tow and start in the high mountains North of the airfield or take a tow to the lower hills in the immediate vicinity of the airfield, but climbing in the upper mountains will take time and sometimes it can be very difficult to get away from the lower hills due to inversion in the valley. With respect to starting strategy I have made a few mistakes in the period I flew at Santa Cilia Jaca. Because I released too early I could not get away further than the local hills.

On other days I towed to the high mountains before the thermals started to develop, which forced me to descend to the lower mountains where I could maintain my altitude until the weather started to develop. I guess I still have to learn a thing or two about flying in this beautiful region.

Climbing to the high mountains North of the airfield is done in three steps: Step 1: the lower hills, Step 2: the middle sized mountains and Step 3: the high mountains, or as you will hear it in the Spanish briefings Escalón 1, 2, 3 (…)

Exciting? Ok, you can read the whole article in the current issue, which you can order here.

The latest issue with top articles for all those who want to be well informed about this wonderful sport: Our new series on powered gliders highlights all aspects of the trendy aircraft, we introduce the new, perfect co-pilot, the brand new app from WeGlide, take a look at the weather situation, flight options, wave flying and flight safety at the Porta and the gravity waves in the low mountain range, get to the bottom of a quick day at the World Championships in Australia, take a look at lightning over the Namib from the cockpit and find out how dangerous a lightning strike can be for a glider, how to protect yourself and what is go and no-go in the vicinity of thunderstorms. However, safety starts before the flight. This is where we find out whether we are really well prepared for the start, whether we are fit and whether we have set up our glider with full concentration and carried out all safety checks conscientiously. To ensure that we get into the air safely, we take a closer look at the take-off dynamics during the winch launch. If you want to fly 1,000 km with an old standard class glider, you can‘t rely on the glide ratio alone: you also need to add some positive energy as our report on the Spanish energy lines shows. Our summer trip to Sweden and our story from the cockpit show why it’s worth sticking to your goals and not giving up so quickly. And now, enjoy reading! Order here.

And here’s a look at the current magazine:

In our new series in the „Flight Safety“ section, we are devoting ourselves to the topic of „motor gliders“. We cover everything from training to the various phases of flight (preparation, take-off, cruising, landing, post-processing) and avoidable emergencies. We will highlight the subtle, but also the clear differences to pure gliding, which can lead to typical accidents in powered glider operations.

With power in the air

Powered gliders are aircraft with one or more engines that can also have the characteristics of a glider when their engines are switched off – this is the official definition. In Germany, Austria and Switzerland, they belong to a separate aircraft category and have specific registrations such as D-Kxxx, OE-9yyy, or HB-2zzz.

The desire to be able to glide well with light aircraft existed early on. After numerous experiments and smaller series, the first „Scheibe Falke SF25“ were launched at the beginning of the 1960s. Of the more than 2000 units built, many are still in use today to acquire numerous class ratings and to extend gliding licenses with TMG approvals or self-launching authorisations.

It goes without saying that the requirements for a self-launch authorisation on a modern high-performance glider are completely different from those on a classic that has been tried and tested for decades. Not only the pure gliding performance plays a role, but also the aircraft geometry and size make different demands. Nevertheless, the engines of the most modern aircraft are sometimes surprisingly similar to the antiquated models from the middle of the last century, which are still powered by the (lawnmower) technology of the time. But more on that later!

An important difference that plays a significant role in training and obtaining ratings is the distinction between „touring motor gliders“ (TMG) and „sailplanes with self-sustainer“.

A touring motor glider (TMG) with a permanently mounted, non-retractable engine and non-retractable propeller must be able to take off and climb under its own power. As a rule, the focus here is on the powered flight characteristics. The Stemme S10/12 with its folding propeller is a major exception. Despite its good cruising characteristics in motorized flight, it also offers excellent gliding characteristics with a glide ratio of more than 50. This unique combination has made the Stemme famous on expeditions far off the beaten track – and stands for a spirit of adventure and boundless passion, as its own advertising says, with certain compromises in the pure gliding characteristics, of course.

Gliders with an auxiliary engine sometimes offer even better gliding characteristics with (almost) no risk of landing. While not all have the capability to self-launch, they may have a glide ratio of 60 or more and are supposedly completely independent. This combination has made them extremely popular over the last three to four decades. Nowadays, almost all current gliders are also available with a wide variety of engines – with all their advantages and disadvantages, as we shall see!

The whole article can be found in the current issue of soaring international

Here we go with our exciting, informative and entertaining reports! We start the season in northern Italy, where numerous airfields offer top conditions for great flights in spring, show you the way from the Arlberg towards Mont Blanc in the “foehn”-wind and reveal a few secrets for perfect slope flying at Porta Westfalica. There we take a look at the lee of the Harz mountains, where waves sometimes are bent and there are climbing areas where you wouldn’t expect them. another surprise is Regtherm: the thermal forecast model will be discontinued by the DWD at the end of March and continued by XC-Therm with 1000 new forecast regions all over Europe. Then we introduce you to ASASys (anti-stall assistance system): The idea is a system that not only warns the pilot better of a stall, but can then also intervene to give the pilot a few seconds to end a potentially dangerous flight condition. Some other pilots see their hobby in danger simply because of their age, but how old is too old? A report by the British Gliding Association answers this question. Another question, whether assembly aids are helpful or risky, is answered by our deputy editor-in-chief. To ensure that everything runs smoothly, here are 13 steps for rigging and de-rigging. It should then also remain relaxed in the air, a sticking point here can be the correct and safe power supply. We show you how to do this using a two-seater. In short, there are a few tips on buying used trailers before we look back 100 years to the “discovery” of thermals. And finally (or perhaps first?), our column invites you to smile and dream a little about the most beautiful hobby in the world. We hope you enjoy reading it! Order here.

And here’s a look at the current magazine:

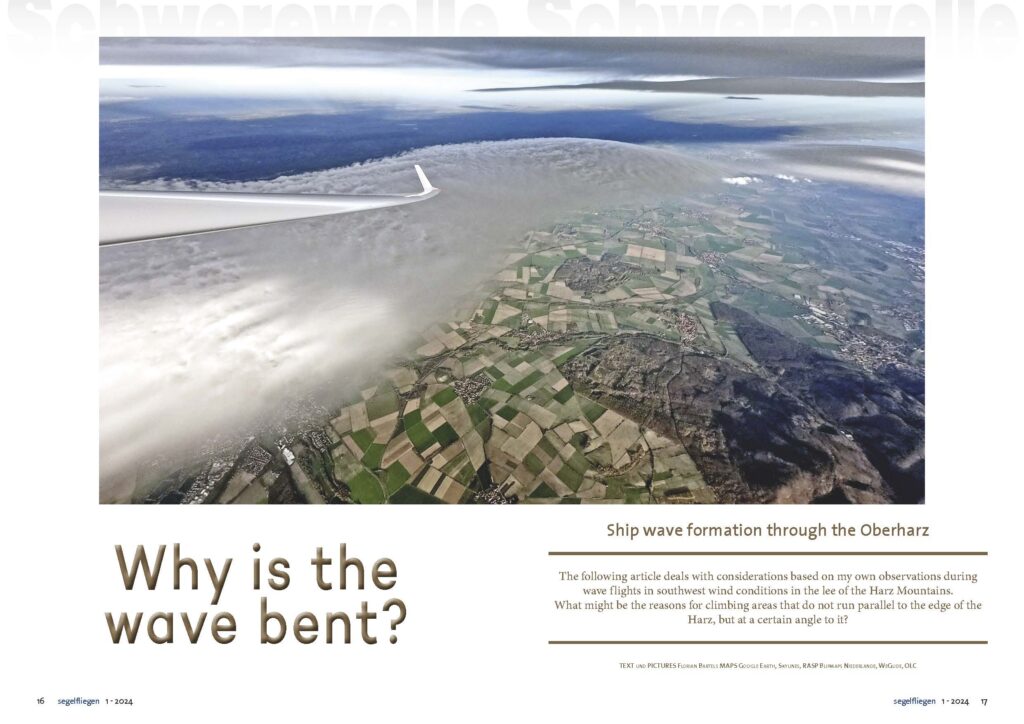

The following article deals with considerations based on my own observations during wave flights in south-westerly wind conditions in the lee of the Harz Mountains. What might be the reasons for wave crests that do not run parallel to the edge of the Harz, but at a certain angle to it?

My observations of wave soaring in the Harz over the last few years show what the title and the lee waves in the Harz are all about. Since the early 2000s, I have been taking off from the “Große Wiese” gliding site on the southern edge of Wolfenbüttel in south-westerly winds in the direction of the northern edge of the Harz in order to enter the waves there.(…)

The shortest route from Wolfenbüttel to the edge of the Harz Mountains near Bad Harzburg is 26 km, the shortest route to the most reliable entry point in Brockenlee is approx. 33 km. In take-off direction 25, the flight path generally leads east of the Oderwald forest towards the south. Here, from the southern end of the Oderwald, it is important to keep an eye on the vario and any clouds, as sometimes usable secondary to tertiary waves form in this area between the Harly mountain range and the direction from Osterwieck to Halberstadt. I always make it my goal to use these waves in gliding and to fly from there to the primary wave at the edge of the Harz.

During a flight on 12.10.2019 with cumulus clouds, I managed to enter the wave at an altitude of approx. 1000 m south of Hornburg after first flying under and then, by flying upwind of the cloud, into a laminar flow on the windward side, which took me above the condensation level. Strangely, the cumulus cloud edges lined up from there did not run parallel to the resin edge (110°/290° orientation), but at an angle of approx. 30° (140°/320°) to it in the direction of Brockenlee. I was thus able to work my way there while maintaining altitude along the cloud lines. On subsequent flights I deliberately tried to repeat this flight path even when there were no cloud indications, which I sometimes succeeded in doing in sections.

If you look at these supporting lines on the chart of the logger, the area deviating from the edge of the resin at a certain angle is clearly noticeable.

But how can this “anomaly”, the deviation from the classic wave updrafts running more or less along the resin edge, come about? I remembered satellite images of islands under cloud cover in the sea, behind which more or less V-shaped cloud formations also form. These wave structures are known as ship waves. The diffraction of the waves changes from a rectilinear V to arc shapes.

The whole article can be found in the current issue of soaring international